MediaCitizen

Friday, May 09, 2025

Trump’s Plan to Give Rabid Right-Wing Propagandists a Global Megaphone

One of President Donald Trump’s top advisers, Kari Lake, just proposed handing far-right propaganda outfit One America News the keys to the newsroom at Voice of America (VOA), a U.S.-funded global news service. As many in the media knuckle down under a repressive Trump regime, this news is another bad sign for democracy and a free press — both at home and abroad.

One America News is a loud and loyal megaphone for everything and anything Donald Trump — including amplifying his “Big Lie” about the outcome of the 2020 presidential election. During general elections, One America News’ founder, Robert Herring Sr., has banned stories about polls that didn’t show Trump in the lead, according to reporting by The Washington Post. It routinely amplifies Trump’s conspiracy theories and doesn’t expend the slightest effort to fact check the president.

Allowing One America News to air its pro-Trump propaganda to VOA’s global audience of more than 360 million people will spread this administration’s authoritarian message worldwide.

Trump’s pattern of First Amendment abuse

This dangerous threat fits neatly into a larger pattern: Since Trump’s inauguration, his administration has abused its authority to bully any news organization that holds the president accountable or questions his far-right agenda. It’s all part of a First-Amendment-defying scheme to transform independent media into White House mouthpieces.

Trump’s ultimatum for the press: Bend a knee before me, or face the consequences. We’re seeing it with the censorship and shakedowns of Trump’s FCC Chairman Brendan Carr, with Trump’s efforts to zero out all public funding for NPR and PBS, and with billionaire media owners like Jeff Bezos and Patrick Soon-Shiong who are all too quick to kiss the ring.

In this most-recent episode, the Trump administration is trying to fire experienced VOA staff, including many journalists, as part of its purge of federal workers from government payrolls — though these moves are being challenged in court.

Many of these actions are blatantly illegal, and likely violations of our First Amendment right to a free press. The VOA charter states clearly that the agency must “serve as a consistently reliable and authoritative source of news” by being “accurate, objective, and comprehensive.” The global outlet has operated with the understanding that its reporting is independent of any strong-arm political pressures from the White House.

“Providing One America News Network to our global audiences makes a mockery of the agency’s history of independent non-partisan journalism,” a former employer of the agency that oversees VOA told NPR.

The graft behind it all

Surrendering the VOA to right-wing conspiracy theorists wouldn’t just turn a global news source into a cruel joke. It’s also an example of the sort of graft that typifies the Trump White House. Gifting a global audience of hundreds of millions to a loyal propagandist will make One America more appealing to advertisers — showing how enabling authoritarianism can be profitable for the few in Trump’s America.

Now that Trump wants to hand One America News the biggest megaphone possible, we need to ask: Are these really the people you want speaking as the voice of America?

The media system Trump and his sycophants envision is decidedly not the one we deserve. Journalists must have the freedom to report news that can inform the public, hold power to account and shine a light on corruption. People have a right to reliable and objective information that allows them to participate fully in democracy.

Independent media is one of the most essential ways we protect democracy from tyranny. With Trump and his cronies constantly on the offensive against the Fourth Estate, it’s time for a broad-based popular movement to demand and defend our right to a free press.

Tuesday, January 21, 2025

The Tech and Media Broligarchs Ready to Serve Trump

President-elect Donald Trump was front and center at the Capitol Rotunda. His family filled the front row. President Biden stood stage left, also surrounded by close family members.

If you think that’s normal, consider the second row.

Rather than the usual file of high-ranking cabinet members and elected officials, Trump held this space for the oligarchy: Side-by-side like vultures on a branch, tech and media billionaires stood in anticipation of their new boss. Their proximity to Trump itself served as a telling predictor of the corruption and decay that’s to come.

The billionaires' row

Closest to Trump stood Elon Musk, who spent at least a quarter-billion dollars during the election for the spot. He presumably offered this largess in exchange for policies and government contracts that could deliver tens of billions of dollars in benefits to Musk properties like Space-X, Starlink and Tesla. Musk transformed Twitter into a MAGA megaphone, and opened the algorithms to neo-Nazis and other bigots and malicious actors who were more than happy to flood X with hate and normalize and defend Trump’s extremism.

To Musk’s right stood Google CEO Sundar Pichai, who bought his company’s spot in the second row via a million-dollar check in support of Trump’s inaugural committee. Pichai’s priorities are to see that the Trump Justice Department abandons two high-profile antitrust lawsuits aimed at breaking Google’s market power. But Pichai was also there to ensure his company has a seat at the table when it comes to shaping AI policy in a Trump-controlled Congress and grabbing some of the billions of dollars in government contracts tied to the advanced technology.

To Pichai’s right stood Amazon Chairman Jeff Bezos and his fiancée Lauren Sánchez. Bezos also wrote a million-dollar check to the inaugural committee. But, of course, his pandering goes further back. Prior to the 2024 election, the Washington Post owner spiked the newspaper’s endorsement of Kamala Harris. He later had Amazon tender a $40 million offer for the rights to produce a documentary on Melania Trump (reportedly outbidding Disney and Paramount). Bezos came for federal contracts as well, seeking among other deals billions in government-launch contracts for Blue Origin, his space venture.

And finally, stood Mark Zuckerberg, who spent the weeks leading up to the inauguration making himself into a pretzel to fit into a shape that Trump might find appealing. That involved almost completely abandoning any prior commitment to content moderation on Meta platforms while mouthing the ridiculous Trumpist belief that fact checking — or any attempt to hold Republicans accountable — is a form of censorship that must be curtailed in the name of free speech.

In addition to writing a million-dollar Meta check for the inaugural committee, Zuckerberg co-hosted the new president during a black-tie reception later in the evening. In exchange, Zuckerberg is hoping for more of the same AI contracts — and expecting Trump to rein in Rep. Jim Jordan and his Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government, which has targeted Meta for allegedly “censoring conservative viewpoints.”

Not to be left out on the grift, Trump issued a “crypto token” days before his inauguration. By swearing in, $TRUMP had reached a value of $15 billion, nearly tripling the new president’s net worth.

When too few control too much media

With so much easy money lying around, it’s not clear whether Trump will have the time or inclination to actually lead the country — or at least address the concerns of the 49.9 percent of voters who chose him in November, as well as those who didn’t. (In case you’re wondering, those concerns are: 1. The economy/inflation, 2. U.S. democracy and 3. national security.)

During his final presidential address from the Oval Office, Biden warned that “an oligarchy is taking shape in America of extreme wealth, power and influence that literally threatens our entire democracy.” Indeed, Biden was on hand at the Capitol to witness this oligarchy's transcendence, his warnings still ringing in the ears of many.

Biden warned that “Americans are being buried under an avalanche of misinformation and disinformation enabling the abuse of power... Social media is giving up on fact-checking. The truth is smothered by lies told for power and for profit.”

The billionaires assembled within reach of the new president were there to assure Trump that they’ll make it so.

Their presence is proof of a systemic failure of the media. A lesson learned: Never again should so few control so many levers of information in our democracy. The work of repairing the damage of the coming years will be hard but essential. But Trump’s inauguration gave a renewed clarity of purpose. A healthy democracy requires a healthy media. And you can’t have that when greedy tech billionaires control far too much of it.

Monday, November 25, 2024

Elon Musk’s Plan to Defund Public Broadcasting and Destroy Accountability

Undermining a publicly funded media system makes perfect sense if clearing a path for graft, corruption and a lack of accountability is the goal. Buried deep in the 10th paragraph of Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy's Wall Street Journal screed on their new Department of Government Efficiency is a line that should worry anyone who cares about the accountability role media must play to sustain the health of any democracy “DOGE will help end federal overspending by taking aim at the $500 billion plus in annual federal expenditures that are unauthorized by Congress or being used in ways that Congress never intended," they write. One of the items in topping their list of targets is the $535-million annual congressional allocation to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the entity that allocates federal funds to public-media outlets across the country Zeroing out federal funding for public media has long been a dream of Republicans. But it’s one that’s never come true. Past efforts have run up against a noisy public, including people of every political persuasion, that believes federal funding for public media is taxpayer money well spent. In 2005, I stood in front of the Capitol Building alongside Clifford the Big Red Dog and then-Sen. Hillary Clinton to protest a George W. Bush-era push to strip public broadcasting of nearly half its funding. “What parents and kids get from public TV is an incredible bargain,” then-Rep. Ed Markey said at the event. “The question is not, ‘Can we afford it?; but rather, ‘Can we afford to lose it?’” Millions of people wrote and called their members of Congress to defend institutions like NPR and PBS, a mass mobilization that succeeded in saving public broadcasting from the ax. The high cost of losing public media Twenty years later, we face similar headwinds. In 2025, Republicans will control the White House, Senate and House of Representatives. They will be acting on the false belief that the November election delivered them a mandate to disassemble the federal government and remake it in Donald Trump’s authoritarian image. But the actual numbers tell a different story. Trump won by a razor-thin margin, securing less than half of the popular vote (a mandate denying 49.9 percent to Kamala Harris’ 48.3 percent). And the Republican majority on the Hill isn’t large enough to dictate such drastic cuts to federal spending; only a fraction of their members would need to defect for Musk and Ramaswamy’s extreme cost-cutting proposals to fail. Having Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene lead the effort in the House is a move that could easily backfire as well. If anything has a popular mandate, it’s the use of federal funds to support public media. Americans routinely rank PBS among the most trusted institutions in the country, and a “most valuable” service taxpayers receive for their money, outranked only by national defense. Moreover, large majorities of the public believe the amount of federal funding that public broadcasting receives is just right, or even too little. Comparatively, this is true. The United States already has one of the lowest levels of federal funding of public media in the developed world — at approximately $1.50 per capita. That’s nothing next to the United Kingdom, which spends more than $81 per person, or France, which spends more than $75. Head further north and the numbers head north as well: Denmark's per-person spending is more than $93, Finland’s more than $100, and Norway’s more than $110. And it isn’t just a European trend: Japan (+$53/capita) and South Korea (+$14) show their appreciation for publicly funded media at levels that put the U.S. outlay to shame. It’s about accountability journalism Trump, Musk, Ramaswamy and their ilk don’t just want to freeze out Frontline and foreclose on Sesame Street, but to pull the plug on every network, station and program that gets public support — from Gulf States Newsroom to the Mountain West News Bureau, from Pacifica Radio to New Jersey Spotlight News. And that’s the point. The Trump purge of federal spending is not just about downsizing the government so billionaires like Musk will have no obligation to pay their fair share in taxes. It’s about stripping our democratic system of all accountability mechanisms, including the sorts of journalism that hold our country’s rich and powerful responsible for their misdeeds. (Republicans are also pushing legislation that would empower President Trump’s Treasury Department to falsely label any nonprofit news outlet as a “terrorist supporting organization” and strip it of the tax-exempt status it needs to survive.) Undermining a publicly funded media system makes perfect sense if clearing a path for graft, corruption and a lack of accountability is the goal. A 2021 study co-authored by University of Pennsylvania professor (and Free Press board chair) Victor Pickard finds that more robust funding for public media strengthens a given country’s democracy — with increased public knowledge about civic affairs, more diverse media coverage and lower levels of extremist views. Moreover, the loss of the quality local journalism and investigative reporting that nonprofit outlets provide has far-reaching societal harms. The Democracy Fund’s Josh Stearns, who’s also a former Free Press staff member, has cataloged the growing body of evidence showing that declines in local news and information lead to drops in civic engagement. “The faltering of newspapers, the consolidation of TV and radio, and the rising power of social media platforms are not just commercial issues driven by the market,” Stearns writes. “They are democratic issues with profound implications for our communities.” For now, Trump, Musk and Ramaswamy are leveraging a lie about a popular mandate to redefine the “public interest” as anything that Trump wants. Trump’s totalitarian dream will not be possible with a thriving, publicly funded and independent media sector. To save this kind of accountability journalism we need people to make as much noise today as they have in the past, and deliver our own mandate for a public-media system that stands against Trump’s brand of authoritarianism.

Friday, November 08, 2024

November's Real Heroes: Election Workers

They’ve endured a global pandemic, power outages and even swarms of bees to help oversee one of the most accurate election processes in the world.

But nothing has presented a larger threat to millions of U.S. election workers and volunteers than the scourge of disinformation coursing across social networks in 2024. Complicating matters further is the small handful of bad actors who seem determined to transform these online lies into acts of violence at the polls and during the vote's immediate aftermath.

This disinformation includes lies about noncitizen voters that some of the most powerful online influencers are spreading, including X owner and reactionary propagandist Elon Musk. Musk is Bad Actor Number One when it comes to amplifying this election falsehood. He marked his second anniversary at the platform’s helm by continuing to boost the false claim that Democrats were transporting hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants into battleground states to skew the vote toward the party's candidates.

Again, none of this is true. “Election experts agree that noncitizens voting in federal elections is virtually nonexistent,” reports Issue One, a national pro-democracy group that works to strengthen and defend the country’s election systems. But that doesn't spare election workers from having to deal with the lie's consequences.

The money driving the disinformation

In its most recent report, Issue One revealed some of the dark web of secretive donors supporting the spread of such election disinformation. It’s a rogues’ gallery of former Trump administration officials with extensive ties to Project 2025, the far-right effort to dismantle U.S. democracy — and the system of checks and balances at its core — and replace it with an authoritarian regime.

Musk himself is a major source of support for the disinformation network. He has funneled tens of billions of dollars into efforts to remake U.S. politics in his image. In 2022, Musk spent $44 billion to take control of Twitter (now X), and has spent tens of millions more in an apparently illegal effort to pay for votes this year in Pennsylvania.

Wired’s Vittoria Elliott recently revealed Musk as the money (more than $100 million and counting) behind a political action committee created to compile and amplify false reports of election fraud — and use these lies to disrupt the vote count. Elliott’s reporting links Musk’s effort with the disinformation-spewing “Election Integrity Network” that Issue One exposed.

Shelter from the storm

In the eye of this tornado of lies stand the election workers themselves.

For years, members of this mostly female civic workforce have warned about threats to their safety. In 2021, the U.S. Department of Justice set up its Elections Threat Task Force to assess threats of violence against election workers and, when needed, prosecute those who act on these threats.

David Becker, founder of the Center for Election Innovation and Research, has led efforts to safeguard U.S. election processes, paying particular attention to the election administrators and public servants who voters encounter as they cast their ballots. “The fact is somehow the hundreds of thousands of election workers and the millions of volunteers who worked on the 2020 election managed the highest turnout we had ever had in American history,” he said during a recent Free Press webinar. And they did so, Becker added, in the middle of a global pandemic.

“Their work has withstood four years of more scrutiny than any election … in world history,” he said. In that time, Becker noted, they’ve been threatened and harassed “not because they did a bad job, but because they did an outstanding job. They’re American heroes in many ways [but] as we head into this election, they're exhausted.”

Unfortunately, these heroes aren't getting any relief from the technology platforms, which have retreated from previous commitments to safeguard election integrity. And this retreat isn’t just happening at Musk’s X.

X is backsliding, but so are other platforms

In an analysis released on Nov. 1, my colleague Nora Benavidez and I found that nearly every platform has avoided dialogue and accountability around the elections. “With few exceptions, the election-integrity problem has worsened since a 2023 Free Press research report found that the largest and most widely used platforms — Meta, X and YouTube — were backsliding on commitments they made in the wake of the 2020 elections, as ‘Big Lie’ content overwhelmed much of social media,” we wrote.

Recent reporting and research indicate a trend of declining social-media engagement on public posts that provide useful information about the voting process, including information that would debunk the sorts of lies that vilify election workers. This trend has been documented most extensively on Meta-owned platforms, including Facebook, Instagram and Threads, that have hundreds of millions of users in the United States.

According to Free Press’ 2024 polling, more than half of voting-age Americans are using social-media apps to access news this election cycle. These platforms have the expertise to implement election-integrity measures. They have the resources to invest in human moderators and staffing. But over and again tech execs like Musk and Mark Zuckerberg demonstrate their true values when they choose not to spend more on election protection.

Poll workers pay the cost of this negligence. Since the 2020 vote, and the false rightwing claims about its legitimacy that followed, many election workers have faced a "campaign of intimidation" from members of the Stop the Steal movement, foreign agents and political operatives.

With more and more people in the United States using social networks as a source of news and information about voting, it falls on companies like Google, Meta and TikTok to stop recycling widely disproved lies about the voting process and stand with election workers in defense of our democracy.

While the concern is real, the swarm of disinformation shouldn't keep people from the polls. “What the voters of this country are experiencing is that voting for the vast majority of people is going to be convenient and easy and secure and safe,” Becker said during the Free Press webinar.

“And that’s the message I really want voters to understand … as some people might be on the fence wondering whether they should turn out or not. Turn out and vote. You’re going to have a good experience.”

Let’s hope he’s right..jpg)

Hoboken voting location, 2024.

Tuesday, April 23, 2024

Trump's FCC Ripped Away Open-Internet Protections. We're This Close to Winning Them Back

A majority of commissioners is set to return to the agency the authority it needs to act as a strong advocate for a user-powered internet.

They will do this by reclassifying broadband-access services as telecom services subject to Title II of the Communications Act. Title II authority allows the FCC to safeguard Net Neutrality and hold companies like AT&T, Comcast and Verizon accountable to internet users across the United States.

Title II authority gives the FCC the tools to make the internet work better for everyone, ensuring that internet service providers can’t block, throttle, or otherwise discriminate against the content everyone accesses online. But it also gives the FCC the regulatory means to ensure that broadband prices and practices are “just and reasonable.” The agency will be able to step in to stop price gouging, safeguard user privacy, protect public safety, eliminate junk fees, and stop other abusive behavior from providers.

“Bringing back the FCC’s authority over broadband and putting back net neutrality rules is popular, and it has been court-tested and court-approved,” she added. “[W]e have an opportunity to get this right. Because in a modern digital economy, it is time to have broadband oversight, national Net Neutrality rules, and policies that ensure the internet is fast, open, and fair.”

Back to the future

The rules up for a vote on April 25 are identical to the 2015 rules. The FCC will enforce them in the same way. And the draft order text that the agency will finalize and adopt already makes this clear — in some cases, going further than the 2015 order did — with a chance before the vote occurs for the FCC to make this language even stronger.

Losing Title II hurt people, which is why millions protested the Trump FCC’s action. Not only did its 2017 repeal gut the Net Neutrality rules, it also surrendered the agency’s power to protect communities from unjust or unreasonable practices by these internet-access goliaths.

This had troubling consequences during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, when Trump FCC Chairman Ajit Pai asked broadband providers to sign a voluntary pledge to preserve people’s vital internet access (he couldn’t force providers to do this since he’d abdicated the agency’s authority to compel these companies to keep users connected). Despite Pai’s claim that the pledge was a success, reporting by Daily Dot found that many of these same companies still cut users’ connections during a national emergency, when everything from work to health care had shifted online.

A 2019 study by Northeastern University and UMass Amherst found that ISP throttling of network services happens “all the time.” Researchers analyzed data from hundreds of thousands of smartphones to determine whether wireless providers were slowing, or throttling, data speeds for specific mobile services. They found that “just about every wireless carrier is guilty of throttling video platforms and streaming services unevenly.”

In everyday terms, this means that companies like AT&T are picking winners and losers online. Allowing such throttling to continue opens the door to more content-based discrimination. This isn’t just about economic favoritism — for example, an ISP slowing down a competitor’s online app so people would use their product instead — but, potentially, the blocking of political messages that gigantic communications companies don’t like.

This isn’t a hypothetical. In 2005, the internet service provider Telus blocked access to a server that hosted a website supporting a labor strike against the company. And in 2011, the Electronic Frontier Foundation found that several ISPs were intercepting user search queries on Bing and Yahoo and directing them to “results” pages that they or their partners controlled.

The say-anything lobbyists

Lobbyists working for these large internet-access companies like to say that Title II authority offers “a solution in each of a problem” that doesn’t exist. And you can bet they’ll repeat a lot of these lies in the aftermath of this week’s vote.

Throughout the 20 years of debate around Title II and Net Neutrality, the powerful phone and cable lobby has demonstrated a willingness to say anything and everything to avoid being held accountable. They’ll say that Title II’s open-internet standard is a heavy-handed regulation that will undermine investment in new broadband deployment; in reality, executives from these companies have said publicly that their capital expenditures aren’t impacted in any way by Title II rules. The lobbyists will say that Net Neutrality is a hyper-partisan, politicized issue — ignoring public polling (see above) that shows internet users on the political left, right, and center overwhelmingly support the sorts of baseline protections offered under Title II.

The fight for this week’s victory predates the Trump FCC repeal of strong Title II rules in 2017. By restoring safeguards that millions fought so hard to make a reality, the FCC is recognizing the broad-based grassroots movement that coalesced in 2005 around the then-obscure principle of Net Neutrality and built a movement focused on retaining the people-powered, democratic spirit that was baked into the internet at its inception.

Without baseline open-internet protections, internet users are subject to privacy invasions, hidden junk fees, data caps, and billing rip-offs from their ISPs. In addition, without Title II oversight the FCC is severely limited in its ability to promote broadband competition and deployment, bringing this essential infrastructure within reach of people in the United States who lack access.

The FCC will change all of that later this week. It will respond to overwhelming public opinion and stand up for internet users against a handful of monopoly-minded companies that for too long have dictated media policy in Washington.

Come Thursday, I and many of the amazing advocates who’ve been fighting this fight for the past 20 years will be on hand at the FCC to witness the final vote. It will be a moment to appreciate our hard work and thank the agency for restoring to Americans their all-important online rights. Join us in celebrating!

Friday, February 23, 2024

To ‘Save Local News,’ Policymakers Need to Understand What Needs Saving

Originally published at Tech Policy Press.

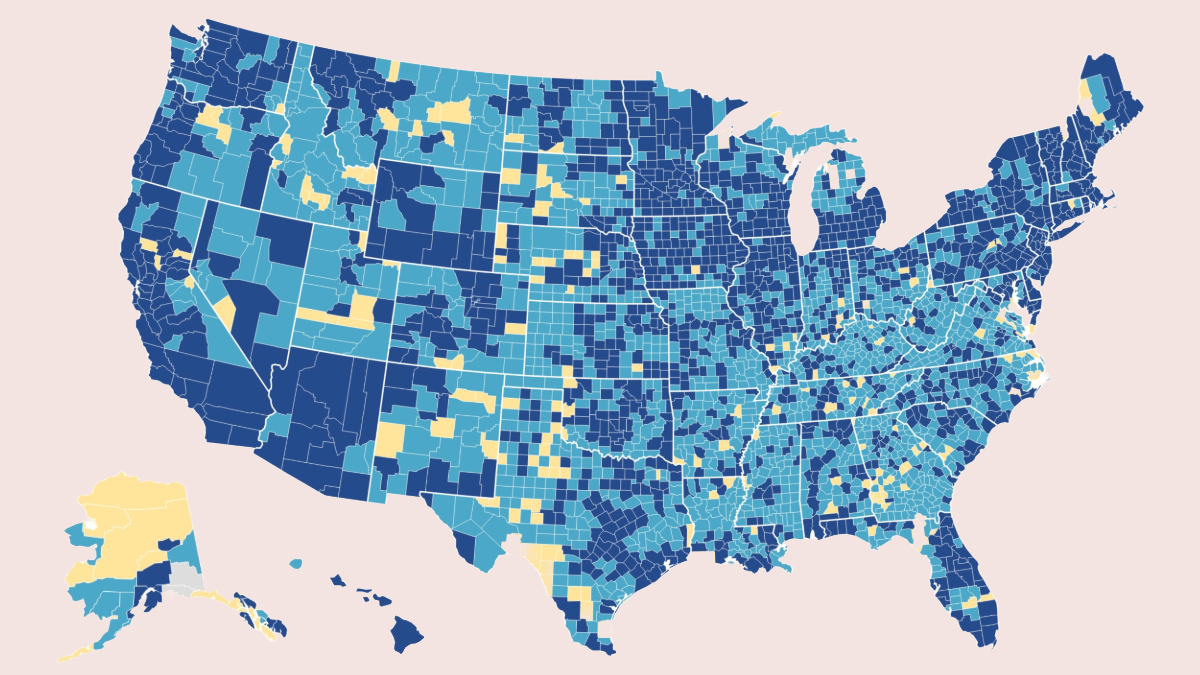

Northwestern Medill Local News Initiative State of Local News 2023

Northwestern reports that the availability of local news depends largely on the wealth of the community where you live. According to project data, counties with an average household income of more than $80,000 can support 10 or more news outlets. Meanwhile, counties with household incomes of $54,000 or less are more likely to be news deserts.

“In communities with little disposable income to put toward news subscriptions or donations and no local philanthropies, cost-cutting becomes the only option,” writes project director Sarah Stonbely. “This creates a self-reinforcing spiral of lower quality and declining readership and, ultimately, closure.”

According to Stonbely, nearly 3,000 local newspapers have shuttered operations over the past two decades, leaving approximately half of the nation’s 3,143 counties with one — or zero — news outlets. 248 more counties are at risk of becoming news deserts in the near future.

Avoid a trickle-down approach

The crisis is real, and policymakers in multiple jurisdictions have started to talk about the roles they can play to solve it — but some of their solutions would do more harm than good. Many of those advocating to save local news in the United States are lining up in support of bills like the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act (JCPA). This legislation would force Big Tech companies like Google and Meta to compensate news publishers for featuring links and content summaries in their search results and on their social networks.

The JCPA (and its California cousin the CJPA, an even worse link-tax plan) take a trickle-down approach to saving local news, awarding big media conglomerates like Fox and “vulture capitalist” funds like Alden Global Capital with large payouts from tech platforms — leaving crumbs for the local and ethnic media outlets that serve lower-income communities.

A recent Free Press Action report finds that California’s link-tax approach (which is also part of a package of bills introduced last week in Illinois) — would result in a massive giveaway to large and very profitable media outlets, including those that focus on spreading hate and disinformation. Meanwhile, independent media outlets, which are closest to the communities they serve and in most need of support, would likely see little-to-no benefit.

“Smaller community-focused outlets are innovating and pushing the entire field of journalism forward, away from the boardroom’s focus on quarterly profits, and toward a future where impact is not measured in revenue growth,” says my Free Press Action colleague and report co-author Alex Frandsen. “Yet any payouts such outlets would receive would be — at best — the leftover crumbs from revenue pies gorged on by already-wealthy media companies.”

And yet ill-conceived Big Tech bargaining and link-tax legislation has captivated lawmakers and some advocates in the United States and other countries, including Australia and Canada.

These bills’ apparent momentum reveals the failure of some lawmakers and advocates to even try to to understand the problem at hand: how to support local news and civic information as the public goods that they are.

Many JCPA and CJPA supporters in the antitrust community seem to support this sort of legislation because it really sticks it to Big Tech, which they see as Public Enemy No. 1. And indeed the big platforms have resorted to some drastic measures to prevent passage of these and similar bills elsewhere.

Political expediency is also driving this legislation forward: these bills have received a forceful tailwind of lobbying support from trade groups representing powerful media conglomerates and commercial broadcasters — the same profitable companies that would benefit from (but don’t actually need) payments from the likes of Meta.

Who should really benefit

What bills like the JCPA and CJPA don’t do, however, is address the real-world impacts of the local-news crisis — which are, as Sarah Stonbely reports, far more acute in low-income communities. These are the same communities that the large media conglomerates lobbying for this legislation have ignored or misrepresented.

Free Press Action has urged lawmakers to reassess the current state of local news instead of trying to turn back the clock to a supposed golden age for journalism that existed pre-internet. We’ve called on legislators to reinvest in programs to fund public-interest media at the local and state levels. Alongside our allies, we’ve encouraged them to replant noncommercial media systems that can and must play a role at a time when the market economics of local news no longer work. And we’ve urged them to reimagine how critical local news and civic information get distributed and to whom, at a time when two local newspapers are shutting down each week and news deserts are spreading, especially in low-income communities.

While lawmakers are right to want to do something to support a more resilient local news and information sector, they need to be explicit about what needs saving and why. Efforts shouldn’t focus on bolstering the established news industry; instead, policymakers should prioritize ways to promote a public good: local-accountability journalism in service of the people who need it the most.

CNN OpEd: Here’s What’s at Risk if Big Tech Doesn’t Address Deceptive AI Content

This voluntary commitment, signed by Google, Microsoft, Meta, OpenAI, TikTok and X, among others, does not outrightly ban the use of so-called political “deepfakes” — false video or audio depictions — of candidates, leaders and other influential public figures. Nor do the platforms agree to restore the sizable teams they had in place to safeguard election integrity in 2020. Even at those previous levels, these teams struggled to stop the spread of disinformation about the election result, helping to fuel violence at the US Capitol Building as Congress prepared to certify President Joe Biden’s victory.

In response, the platforms have pledged to set high expectations in 2024 for how they “will manage the risks arising from deceptive AI election content,” according to the joint accord. And their actions will be guided by several principles, including prevention, detection, evaluation and public awareness.

If the platforms want to prevent a repeat of 2020, they need to be doing much more now that technology has made it possible to dupe voters with these deceptively believable facsimiles... [read the full commentary at CNN]

Friday, November 17, 2023

How the Media Can Atone for Enabling the Rise of Trumpism

For far too long, media execs have played along with Donald Trump’s strongman charade, aware that his tele-presence is a boon for ratings and revenues. Now, U.S. democracy is reaping what they have sown.

At a speech delivered on Veterans Day, Trump used rhetoric nearly identical to that used by Adolf Hitler 80 years earlier.Rather than honoring veterans as one might expect of a political speech on this day, Trump used the occasion to label his adversaries “vermin” — promising that, if elected, he would use his power to “root out” all his political enemies.

The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake found the parallels: Hitler frequently used vermin references to justify the murder of Jews and others across Europe, while “Trump has used it more broadly to suggest that his opponents are subhuman” and deserve punishment.

Parroting Hitler should not be considered normal behavior in any U.S. election cycle. But the media have grown used to covering Trump’s extremism as if it’s standard political fare. This time, though, some journalists rightly saw his Veterans Day speech as very dangerous.

“It’s important to emphasize that Trump’s rhetorical excesses are not new. To know anything about the Republican is to know that he, on a nearly daily basis, finds new and needlessly provocative ways to shock, offend, insult, and degrade,” wrote Steve Benen for MSNBC.

What is new, however, is the growing number of reporters and commentators being more explicit in their use of the term “fascist” to describe Trump’s beliefs — and “dictatorship” to describe what his return to power would represent for the future of U.S. democracy.

The media aren’t sounding these sorts of alarms enough, according to Margaret Sullivan, who wrote about the mounting evidence that Trump is indeed a fascist. “The press generally is not doing an adequate job of communicating those realities,” she said. “Instead, journalists have emphasized Joe Biden’s age and Trump’s ‘freewheeling’ style. They blame the public’s attitudes on ‘polarization,’ as if they themselves have no role.”

Sullivan urges more members of the press to report on the dark prospect of a second Trump presidency. They should “ask voters directly whether they are comfortable with [Trump’s] plans, and report on that. Display these stories prominently, and then do it again soon,” she wrote.

The ‘F’ word

Sullivan is right, of course. The media need to report more on the rise of fascism in America, and they also need to reflect on their role in enabling this.

For decades the former president has capitalized on the media’s obsessive attention to paint an alternative vision of himself — one in which he features not as a twice-impeached, criminally indicted sexual abuser who sought to overthrow a democratic election that he lost, but as a decisive and winning strongman, the only person with the power and charisma to make America great again.

In 2016, then-CBS CEO Les Moonves said that devoting so much airtime to then-candidate Trump “may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.” At the time, Moonves was praising Trump for the bumper crop of political-ad dollars brought in during the contentious 2016 election, but he was not alone.

Former media executive Jeff Zucker has arguably done more than any single person to burnish the 21st-century caricature of Donald Trump. While an executive at NBC, he greenlit The Apprentice, which remade Trump from a bankruptcy-spawning loser into a boardroom genius with impeccable business savvy.

When Trump entered the political fray in 2015, he did so with an Apprentice tailwind. Zucker, who by then had transitioned to the top job at CNN, trained the network’s cameras on his celebrity candidate while denying equal time to Trump’s Republican opponents. Ratings were also Zucker’s rationale for keeping Trump center stage in 2016.

The media chose Trump in 2016 well before most Republican voters had a chance to vote for any of the other GOP candidates in the race.

And it didn’t end there. In 2020, Mathias Döpfner, head of German media giant Axel Springer, sent a message asking the company’s executives if they wanted to “get together for an hour on the morning on Nov. 3 and pray that Donald Trump will again become President of the United States of America.” Döpfner justified this question by praising the Trump administration for supporting issues, like corporate tax breaks and reining in big tech, that benefitted Axel Springer.

The profit incentive

If you’re noticing a pattern, it’s this: Democracy suffers when a commercial media system showcases fascist demagogues for profit.

That seems obvious enough, but it’s worth repeating: News media companies rely on ratings and related advertising revenues to survive. In other words, the news business is about putting on a show that will draw the largest numbers of viewers. And Trump — like Hitler and Mussolini before him — is a camera-ready showman.

More important matters like correcting Trump’s many falsehoods or reporting on the troubling consequences of a second Trump presidency are secondary for those who just want to draw more attention to their primetime offerings.

Former executives, like Moonves and Zucker — who for a variety of unsavory reasons have since left their companies — and existing ones, like Döpfner, were saying that as long as Trump’s autocratic extremism made them richer, there was no need to worry about the consequences. Never mind that, if elected, he’d likely use his power to undermine media freedom and silence dissenting voices.

The commercial U.S. media system needs to undergo deep reckoning for accommodating the rise of Trumpism. This atonement should be reflected in a shift in the ways large outlets report on Trump, but also by recognizing the commercial incentives that drive media to lead with the Trump Show, damn the far-right repercussions.

Without calling themselves to account for the damage they’ve done, media executives will never quit their Trump habit — not in 2024, nor at any point after.