Originally published at Tech Policy Press.

Northwestern Medill Local News Initiative State of Local News 2023

Northwestern reports that the availability of local news depends largely on the wealth of the community where you live. According to project data, counties with an average household income of more than $80,000 can support 10 or more news outlets. Meanwhile, counties with household incomes of $54,000 or less are more likely to be news deserts.

“In communities with little disposable income to put toward news subscriptions or donations and no local philanthropies, cost-cutting becomes the only option,” writes project director Sarah Stonbely. “This creates a self-reinforcing spiral of lower quality and declining readership and, ultimately, closure.”

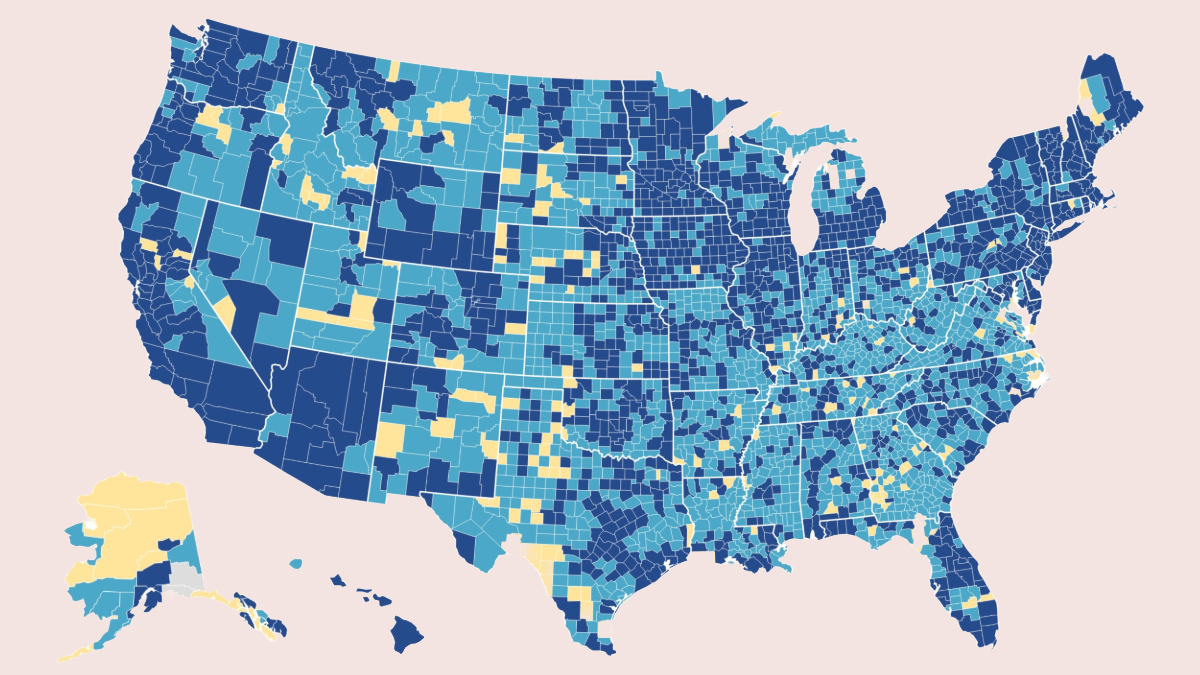

According to Stonbely, nearly 3,000 local newspapers have shuttered operations over the past two decades, leaving approximately half of the nation’s 3,143 counties with one — or zero — news outlets. 248 more counties are at risk of becoming news deserts in the near future.

Avoid a trickle-down approach

The crisis is real, and policymakers in multiple jurisdictions have started to talk about the roles they can play to solve it — but some of their solutions would do more harm than good. Many of those advocating to save local news in the United States are lining up in support of bills like the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act (JCPA). This legislation would force Big Tech companies like Google and Meta to compensate news publishers for featuring links and content summaries in their search results and on their social networks.

The JCPA (and its California cousin the CJPA, an even worse link-tax plan) take a trickle-down approach to saving local news, awarding big media conglomerates like Fox and “vulture capitalist” funds like Alden Global Capital with large payouts from tech platforms — leaving crumbs for the local and ethnic media outlets that serve lower-income communities.

A recent Free Press Action report finds that California’s link-tax approach (which is also part of a package of bills introduced last week in Illinois) — would result in a massive giveaway to large and very profitable media outlets, including those that focus on spreading hate and disinformation. Meanwhile, independent media outlets, which are closest to the communities they serve and in most need of support, would likely see little-to-no benefit.

“Smaller community-focused outlets are innovating and pushing the entire field of journalism forward, away from the boardroom’s focus on quarterly profits, and toward a future where impact is not measured in revenue growth,” says my Free Press Action colleague and report co-author Alex Frandsen. “Yet any payouts such outlets would receive would be — at best — the leftover crumbs from revenue pies gorged on by already-wealthy media companies.”

And yet ill-conceived Big Tech bargaining and link-tax legislation has captivated lawmakers and some advocates in the United States and other countries, including Australia and Canada.

These bills’ apparent momentum reveals the failure of some lawmakers and advocates to even try to to understand the problem at hand: how to support local news and civic information as the public goods that they are.

Many JCPA and CJPA supporters in the antitrust community seem to support this sort of legislation because it really sticks it to Big Tech, which they see as Public Enemy No. 1. And indeed the big platforms have resorted to some drastic measures to prevent passage of these and similar bills elsewhere.

Political expediency is also driving this legislation forward: these bills have received a forceful tailwind of lobbying support from trade groups representing powerful media conglomerates and commercial broadcasters — the same profitable companies that would benefit from (but don’t actually need) payments from the likes of Meta.

Who should really benefit

What bills like the JCPA and CJPA don’t do, however, is address the real-world impacts of the local-news crisis — which are, as Sarah Stonbely reports, far more acute in low-income communities. These are the same communities that the large media conglomerates lobbying for this legislation have ignored or misrepresented.

Free Press Action has urged lawmakers to reassess the current state of local news instead of trying to turn back the clock to a supposed golden age for journalism that existed pre-internet. We’ve called on legislators to reinvest in programs to fund public-interest media at the local and state levels. Alongside our allies, we’ve encouraged them to replant noncommercial media systems that can and must play a role at a time when the market economics of local news no longer work. And we’ve urged them to reimagine how critical local news and civic information get distributed and to whom, at a time when two local newspapers are shutting down each week and news deserts are spreading, especially in low-income communities.

While lawmakers are right to want to do something to support a more resilient local news and information sector, they need to be explicit about what needs saving and why. Efforts shouldn’t focus on bolstering the established news industry; instead, policymakers should prioritize ways to promote a public good: local-accountability journalism in service of the people who need it the most.